Most discussions of the UK’s ‘No Recourse to Public Funds’ immigration rule would suggest that its origins lie in the Immigration and Asylum Act 1999. The current iteration of the policy, which prevents people ‘subject to immigration control’ from accessing most welfare benefits and homelessness assistance, can indeed be found in this 1999 Act. Yet, in tracing the restriction only so far back as this, we miss the historical antecedents of ideas about deservingness which long pre-date this statute.

Looking back to the 1905 Aliens Act

In 1905, during the second reading of the Aliens Bill (later to become the 1905 Aliens Act), the Conservative British Prime Minister Arthur Balfour asked the House of Commons, “Why should we admit into this country people likely to become a public charge?”. Balfour’s question, shored up with ideas of “diseased” and “intrinsically undesirable” people ‘polluting’ the British nation, takes us to the heart of the 1905 Aliens Act, Britain’s first modern immigration act.

This defining piece of legislation drew Britain’s borders primarily along the lines of who was and who was not deemed to be a ‘drain’ on public funds. The 1905 Alien’s Act was introduced in response to Jewish migration from Eastern Europe, when increasing numbers of Jewish refugees were fleeing the Russian Empire for Britain.

In the decades leading up to the passing of the Act, there was increasing social anxiety around the figure of the ‘destitute’ Eastern European Jew. This figure was repeatedly constructed as a problem in popular and political discourse, with the interests of the indigenous working class population frequently pitched against those of the ‘pauper alien’, who was held responsible for a host of social issues such as rising unemployment and low wages. “They drive our own people into the workhouse or, still worse, into vagabondage”, wrote the writer S.H. Jeyes in a paper published in The Destitute Alien in Great Britain: A Series of Papers Dealing with the Subject of Foreign Pauper Immigration (1892: 185). Continuing, Jeyes summarised the problem as such: “In giving asylum to them we are turning Englishmen out of their own homes”. This narrative, cultivated by Conservative politicians, newspapers and groups such as the far-right British Brothers’ League, became pervasive in late nineteenth and early twentieth century Britain.

The ‘undesirables’

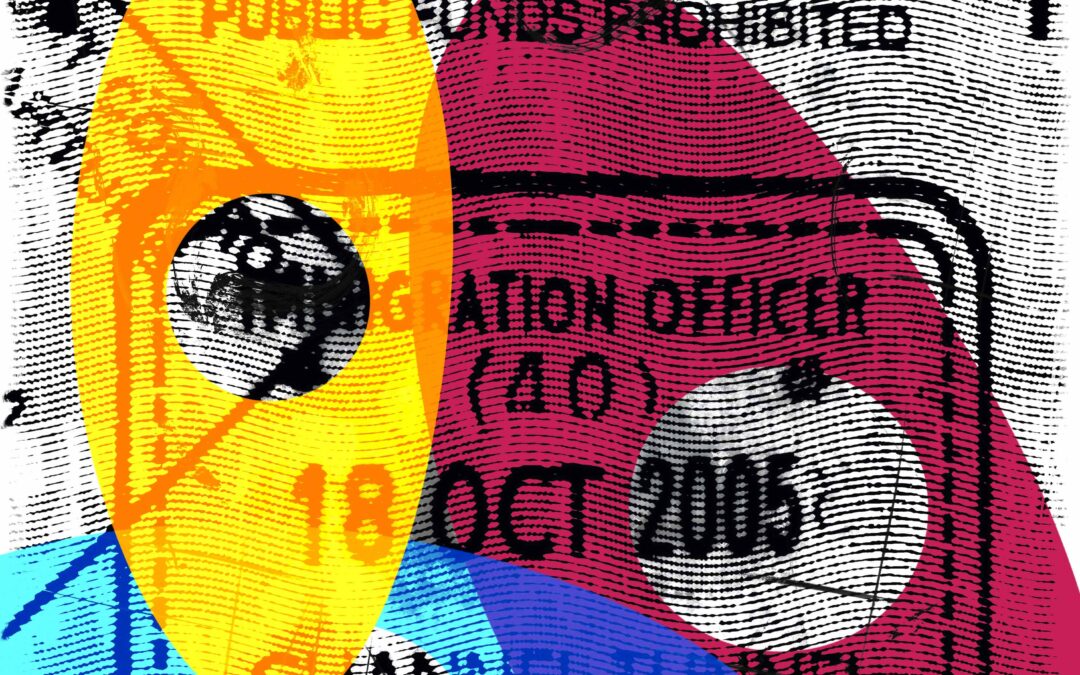

Against this backdrop, the 1905 Aliens Act determined the parameters of the “undesirable immigrant” who was to be refused entry into the country. Those deemed “undesirable” to the nation included anyone who was unable to show that they could support themselves and their dependents; those who were “lunatics”, “idiots”, or suffering from disease or infirmity and likely to require public funds or otherwise become ‘a detriment to the public’ (Aliens Act, 1905). It was this statute that brought immigration officers into being: state actors who were given the power to refuse entry to ‘undesirables’. Many migrants were subsequently turned away at the border due to lack of means.

The Act also introduced internal border controls, which gave the government the power to deport any “alien” that a court found to be in receipt of parochial relief, “wandering without ostensible means of subsistence” or living in overcrowded and unsanitary conditions. Those convicted of criminal offences were also liable for deportation.

The entanglement of immigration and welfare controls

Since the beginning of modern immigration legislation in Britain, border controls and the question of who is considered to be deserving of welfare support have been thoroughly intertwined.

The Aliens Act 1905 paved the way for subsequent welfare restrictions based on residency and nationality requirements, such as the 1908 Old Age Pensions Act. This Act extended internal controls and left many Jewish migrants without pensions. Further policies in 1919 and 1921 prohibited ‘aliens’ from accessing unemployment benefit payments. These early self-sufficiency requirements and welfare restrictions laid the foundations for successive immigration controls on welfare, such as the contemporary welfare exclusions we focus on as part of our research for the ‘Migrants and Solidarities’ project.

For example, the No Recourse to Public Funds (NRPF) rule with which I began this blog, which was first introduced into legislation in 1971. Like the 1905 Aliens Act, the NRPF rule was initially used to deny migrants entry into Britain by requiring them to be ‘self-sufficient’ to ensure that they would not need ‘public funds’. Later, after numerous attacks on migrants’ rights to social security, it became a fundamental policy excluding migrants already within the nation state from welfare support, leaving many people – particularly those from former colonies of the British Empire – destitute and indebted.

Thinking historically

In tracing this very brief history of the inseparability of immigration and welfare regimes, we can see the importance of grounding our understanding of current migration policies within a historical framework and avoiding the ‘trap of presentism’ (Walters, 2010), which might view the current mechanisms of exclusion in operation as ‘new’.

By taking a historical lens, we can understand and disentangle the neglected histories of current policies restricting migrants’ access to welfare. At the same time, thinking historically allows us to attend to the complex construction of ideas such as ‘(un)deservingness’ over time. This was something Karen Goodman reminded us of at the first meeting of our Stakeholder Knowledge Exchange Board, where she invited us to think about how contemporary understandings of (un)deservingness in Britain have been shaped by the Poor Laws of 1834.