Silke Zschomler with Leidy Marin Agudelo, Tatjana Moskvina, Akbar M. Delshad, Basir Samim, Duaa Alfadzli

*

Over the past months, I have been working collaboratively on a photovoice project with a group of adults who have migrated to, or come to seek sanctuary in, London and who are attending English language classes to help them with navigating their everyday realities and make their lives in the city. The idea of the project was for those who participated to have an opportunity to take photographs to share their ideas, opinions, and points of view on their language learning experience; how they feel about living, belonging, connecting with others in London; and how support and solidarities across difference might be enriched in the context of language learning.

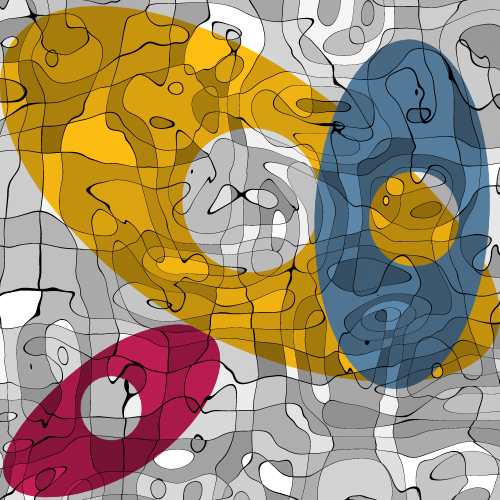

We examined and traced different experiences of migrant language educational spaces becoming sites for rehumanising social relations and a catalyst for a supportive sociality from the bottom up, something I discussed in a previous blog post. Over the course of the summer, it became evident that the photo project was not only a vehicle to explore the forging of such bottom-up sociality. The project itself became an integral part of it – a vehicle for generating solidarities across ethnic-cultural-linguistic boundaries, heterogenous backgrounds and experiences, different mobilities and migratory trajectories. In what follows some of the members of the photo project share reflections on the connectedness, togetherness and mutual support that makes their English classes an important part of their lives. These reflections were sparked by this photograph taken by Leidy, one of the project participants, to express her experience of attending English classes.

*

We are all very different. We come from different countries and some of us have lived in other countries before coming to the UK. We speak different languages and eat different kinds of food. Some of us have been in London for some time, others have only lived here for a short time, and we all have different passports, papers, and statuses. What we have in common is that we all come to class to learn English. For all of us this is a very important experience. We want to learn. We want to understand each other. Early in the project we were thinking of and mapped the different communities we are part of, created pictures of them and made collages – in all of our collages our English classes played a key role! Let us tell you why.

When you come to class you learn English and the grammar, you see people and you speak and improve English, but what is important is that you are making friends. Making friends is really important! You need to feel that you are with someone. You need this emotion, this feeling of togetherness. The English class helps a lot – it is a place where you can belong! Maybe it is only two hours, but it means a lot. Tatjana said, ‘I go to class with smile – my heart smiles!’. Many of us feel that when we come to class we can connect from heart to heart, others really see you and you see them. There is dignity and respect, and you feel valued. For us, this is very beautiful, like in spring, like sunshine, it gives us a lot of hope!

Sometimes your life is not easy, maybe you don’t feel very comfortable in your new place and people are not always nice and friendly to you. You have these moments when you feel alone, and you feel like you are not part of anything. Also, we all have our problems, maybe with the home office, the council, the job centre, maybe with our health or when we think of our families and people and places we had to leave behind. There can be many depressing situations. We all have our struggles with different things and problems, but we want to help and support each other. We try to create something positive together, transfer good things to each other, to give us strength for difficult things and times. In the class and in the photo project there is empathy and kindness – a lot of kindness and care. Akbar said, ‘It is like medicine!’

Normally the people in your class are kind – very, very kind – and you can always speak with them. In this way, you can connect to so many people from everywhere. That’s what’s amazing about English classes: you can meet and get to know so many different people. It is so mixed and diverse. You can ask about other experiences and cultures. Through this you can grow, you can change your mind and become more open and more confident to engage with others. It’s about trust and solidarity. You are not afraid anymore. It feels like many windows are opening. You are making new connections, good connections, and building new friendships – our London becomes bigger and keeps expanding!

These reflections highlight the potential for migrant language educational settings to work as emergent spaces in which a more sociable kind of being in the world and relating to one another become viable. In the experience of Leidy, Tatjana, Akbar, Basir, and Duaa, their English classes function as an affective community, as inclusive, hospitable, and kind places where relationships are revalorised, positive affects circulate, and negative affects and experiences of exclusion, hostility, and other struggles that are part of navigating the complex processes of setting up a new life in the city can be counteracted. This is of course not always the case and does by no means happen automatically or between everyone who attends English classes which also came up during our conversations. As I discuss in my previous research, prejudice and discriminatory attitudes from wider society easily seep into migrant language educational settings and can be reproduced within classroom walls. Thus, the experiences the project members reflected on above intersect or co-exist with experiences of othering, inequitable relations, and different exclusionary discourses and mechanisms that students encounter. However, the point we would like to make here is that as these English classes often become an integral part of migrants’ social networks, they engender possibilities for cultivating empathy and care as well as for nurturing connections, friendships, and solidarities across difference within the migrant metropolis.

What the members of the photo project shared resonates well with observations of teachers in my previous research. When describing their experiences of teaching in migrant language educational settings, they frequently highlighted the ‘social or sociable aspect’ of these English classes and the ‘warmth of the students’ that made teaching ‘a bit more natural’. They often spoke about ‘a tremendous sense of unity’, ‘a kind of human companionship and friendship’, ‘a kind of socialising that goes beyond just getting on with one another’ and a ‘certain kind of class spirit’ – something they had not encountered when teaching in other settings.

In his commentary on place-based solidarities in diversity, Stijn Oosterlynck (2018) advocates for an increased focus on micro-level practices and encounters – on ‘how people mobilise different sources of solidarity in their attempts to take shared responsibility for the concrete places where they live, work, learn and play together in superdiversity’. The above reflections offer a glimpse of what this can look like and entail in the context of migrant language educational settings. Here, the joint practices that the heterogeneous student body engage in are located in relationally constituted places and can foster feelings of togetherness, belonging, and mutual support. When such feelings are fostered and the supportive sociality as described and experienced by the photo project members comes to fruition, these places become sites of innovative forms of solidarity within everyday negotiations of diversity and difference and the place-based struggles of the migrant metropolis.

The photo project is part of Silke’s postdoctoral fellowship: ‘From ‘language learning as the key to integration’ to ‘language learning for enriching solidarities in diversity’.